Anchors Away

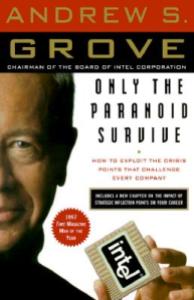

In 1985, Intel was a semiconductor memory company. It had been a memory company for 17 years, but Japan was making memory better and cheaper and Intel was bleeding money trying to keep up. After over a year of experimenting with futile strategies, president Andy Grove and CEO Gordon Moore fired themselves.

They walked outside, smoked a couple cigarettes, and then walked back in pretending to be new hires. The pretend-new CEO and president didn’t know that Intel spent 17 years selling computer memory. They took one look at the company, killed the memory business, and used their freshly-freed talent to become a microprocessor company.

Anchoring is a cognitive bias that forces people to focus on some initial value and then make decisions with that reference. A good salesman often quotes an inflated price and then allows the customer to negotiate a much lower price. Because the customer has the initially-quoted price as an anchor, the new price seems like a great deal.

Anchors are the root of loss aversion. A decade ago, I had a huge losing position in a crappy company called Sun Microsystems. I started out with high hopes that Java could take down Microsoft, but the best they could do was sue Microsoft for being a monopoly.

As a novice investor, I didn’t want to realize my loss. If I didn’t sell Sun, it was hypothetically still worth my anchoring purchase price (even though the market was trading at half that). My very smart labmate Andy asked me: If you didn’t already own this stock, would you buy it today?

Of course not. It was a shitty company and nobody liked Java.

So sell it.

Avoid anchoring biases by framing the situation in a new perspective. If your employer fired you, is this the job you would look for today? If not, quit. If your spouse died, is this the replacement you would look for on OKCupid? If not, leave. If your child died, would you make another one? If not, put it up for adoption.

If you were starting a new company, is this the one you would start today?

2. Anchoring, the Mother of Behavioral Biases –Psy-Fi