Contracts, Code, and Complexity

The right to be sued is the power to accept a commitment. -–Thomas Schelling [1]

No one’s gonna do business with you without knowing they have recourse for when you try to weasel out. Even 5000 years ago, people created contracts on clay tablets so that they had something to take to the king if the counterparty welched.

Humans are opportunistic. Over time, people learned to be weasels. Some people learned to be exceptionally good weasels. Beginning in ancient Athens, these people were called lawyers (actually they were called orators, but served the same purpose).

Orators were paid well. Athenians knew that having a good lawyer could be a huge competitive advantage. If your counterparty hires Demosthenes to plead his case, then you’d better put Cicero on retainer.

Since then, litigation has been an arms race. 40% of Oracle’s headcount is employed on the legal team, and only because its friends Google and Microsoft invest just as much. Google spends $17 million a year on federal lobbying. The top issue? Patent protection.

As Karl Marx astutely observed, Competition is wasteful.

But competition does have one redeeming quality: It enables evolution. Without competitive exclusion, there would be no reason for natural selection and we’d all still be protozoa swimming in a primordial soup.

Instead, we’re complex organisms who know how to be weasels.

And it’s because counterparties spent 5000 years being weasels that contracts, and the laws governing contracts, have become so complex.

You don’t know the rule until you know its exceptions. In practice, the exceptions to the rule are the rule.

Contractual complexity is good. Complexity allocates responsibility and risk for the possible complications that might arise. This increases predictability, which allows counterparties to put more at stake.

While complex, the contracts and legal codes we have today provide better risk management than clay tablets and the Code of Hammurabi.

As the stakes increase, so does the cost of litigation. At some point humans began to think, Securing a commitment through legal coercion is expensive! Can we can have predictable risk allocation without using the threat of litigation? Maybe we don’t need the right to be sued in order to accept a commitment. Maybe a commitment can be self-governing.

A smart contract enforces a commitment without resorting to the threat of external litigation [2].

Early smart contracts won’t be robust against weasels, just like early clay tablets weren’t robust against Demosthenes. That’s why people didn’t put a lot at stake on a clay tablet. It was certainly no reason to throw out clay tablets!

It took 1600 years to go from the publican business partnerships in Rome to the Honor del Bazacle [3], the first modern joint-stock corporation. Romans had the technology to draft a corporate charter on papyrus; what they lacked was centuries of cumulative knowledge on how to structure a corporation.

Complexity has to be earned. Otherwise, it’s obfuscation. The Honor del Bazacle charter was complex because it had evolved the ability to protect its beneficiaries [4]:

Most early financial documents were fairly succinct records. Why would it take eight feet of tiny script to create a corporation?

…

The corporation is an organization that is designed to operate autonomously, perhaps for several centuries. The Honor del Bazacle charter is like a complete set of rules for playing a game: These rules needed to ensure that no single player, either unintentionally or willfully, could ruin the game or cheat the other players.

As a result, the Bazacle is an enterprise that still stands today.

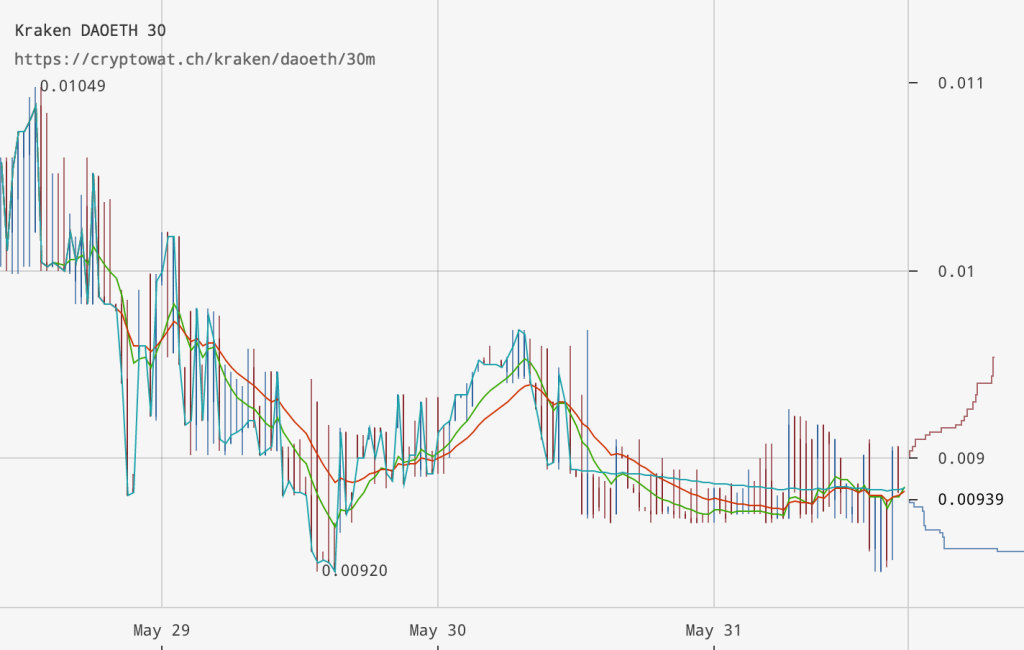

Last week, TheDAO put a corporation into a smart contract, and a weasel took a bunch of its money. Now its participants are pleading for an Ethereum fork that erases an unpredicted, but not unpredictable, outcome.

I have DAO tokens. I prefer that the “hacker” keep whatever ether I lost. The great thing about smart contracts is the predictable risk allocation. I signed up for the risk of losing my ether. I did not sign up for third-party adjudication.

The transaction-erasing fork will ultimately be decided by Ethereum miners, who can choose whether to adopt it in a software update. In a way, they serve as a decentralized parliament. But as someone who operates a mining node, I don’t want to be a parliamentarian. I didn’t sign up for that and I’m not qualified.

Blockchain contracts are not about adjudication by vote; we already have a very good solution for that in the modern court system. They’re about giving two parties the ability to trust a commitment. I want the rights and responsibilities that I signed up for.

References:

1. Thomas Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict. 1981.

2. Nick Szabo, Formalizing and Securing Relationships on Public Networks. 1997.

3. Germain Sicard, The Origins of Corporations: The Mills of Toulouse in the Middle Ages. 2015.

4. William Goetzmann, Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible. 2016.